AttributionThis homily is unusual in that it relies heavily on a single passage from a single book. The book in question is Dr. William Barclay's

The Gospel of Mark, Revised Edition. The passage occurs on pages 260-262. This revised commentary on Mark's Gospel was published over thirty years ago, in 1975. One of the nicest gifts I received after ordination was a complete, brand new, set of Barclay's New Testament commentaries from a fellow deacon, Lynn Johnson. However, this marks only the second time I have used Barclay for preaching. His commentaries, however, are wonderful for personal study of the books of the New Testament.

Readings: Jer 31,7-9; Ps 126,1-6; Heb 5,1-6; Mk 10,46-52Even a merely human high priest, the author of the Letter to the Hebrews tells us, because he is conscious of his own weakness, "is able to deal patiently with the ignorant and erring" (Heb 5,2). The point being made is how much more patient and merciful is Jesus Christ, our High Priest, who, as we recited last Sunday from this same New Testament letter, is able "to sympathize with our weaknesses” because he has been "tested in every way, yet is without sin" (

Heb 4,14-15). This gets to the core of our confession, which the author of the Letter to the Hebrews tells us: "hold fast" (

Heb 4,14).

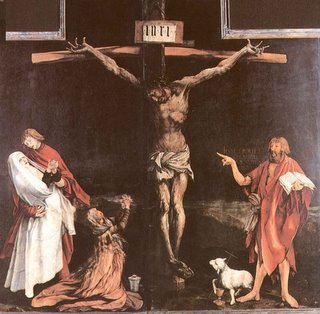

But holding fast to our confession, "Jesus is Lord," stands in stark contrast to what today’s Gospel calls us to do, which is to follow Jesus on the way to God’s Kingdom. Like most of the episodes of Jesus’ life written down by the evangelists, today’s

pericope concerning the blind man finds its meaning for us not primarily in the event itself, but beyond it. Like so many scriptural passages, this passage is about each of us and tells us a lot about Jesus Christ and how he relates to us. In St. Mark’s Gospel, as well as the other two synoptic Gospels, Matthew and Luke, our Lord makes only one trip to Jerusalem during his public ministry. Today’s passage takes place during this journey, which ends at Passover with his betrayal, arrest, trials, scourging, and crucifixion. The city of Jericho is about 15 miles east of Jerusalem, or, given its location on the West Bank of the Jordan River, just down the mountain. Jewish law during the Second Temple period, during which Jesus lived, required every male Jew twelve and older, living within approximately 15 miles of Jerusalem, to observe Passover in the holy city (Barclay,

The Gospel of Mark, Revised Edition, pg 260). Despite this requirement, it was not possible that all could attend. Since the vast majority of Jewish pilgrims going to Jerusalem from the North passed through Jericho, walking along the Jordan so as to avoid setting foot in Samaria, the men of Jericho who were not making the pilgrimage would line the streets in order to wish the pilgrims well.

Similarly, when a distinguished Rabbi walked such a journey it was normal that he was surrounded by a crowd of people; in the case of Jesus this crowd included both men and women, which was not the norm at all. The crowd constituted the teacher’s disciples, who listened to him as he taught while walking. It is easy to imagine the excitement among the residents of Jericho when they received word that Jesus of Nazareth, the audacious young Galilean who was healing the sick, casting out demons, and who had pitted himself against the religious authorities throughout Galilee, was passing through town. The tension was made even greater given that many priests and Levites who took turns ministering at the Temple lived in Jericho, thus constituting a large group of those religious authorities.

At the northern gate of Jericho sat a blind beggar, Bartimaeus, the son of Timaeus. Upon hearing the "sizeable crowd" as they approached the gate to leave the city, Bartimaeus asks who is passing by. When he is told that it is Jesus of Nazareth we receive an indication that Jesus’ fame had spread beyond his native Galilee when the blind man suddenly cries out, "Jesus, son of David, have pity on me" (Mk 10,47). Upon hearing his loud cry many rebuked him and told him to be silent or, more realistically, they told him to shut up. In his encounter with our Lord there are five lessons we learn from Bartimaeus, the blind beggar, a marginal Jewish castoff who lived over 2,000 years ago, about prayer.

The first lesson is persistence. Once Bartimaeus knew who was passing by, nothing would stop him from coming face-to-face with Jesus. His was not a nebulous, wistful, curious desire to encounter this Galilean miracle-worker. Encountering Jesus was his deepest and most desperate desire; deaf to the voices seeking to silence him, this wretched soul keeps calling out, "Son of David, have pity on me." (Mk 10,48). Then, above the noise, our Lord hears the cries of this poor, blind beggar and calls Bartimaeus to him. The beggar’s response to the call of our Lord is our second lesson.

Immediately and with no hesitation, the blind man, Mark tells us, "threw aside his cloak, sprang up, and came to Jesus" (Mk 10,50). As we see in other Gospel narratives, like the one from two Sundays past, found in this same chapter of St. Mark, when Jesus calls the rich young man to follow him, many hear the call of the Lord, but say in effect, "Wait until I have done this, or finished that." Our inordinate attachment to ourselves, or, as appears to be the case with the rich young man, things, keep us from springing up and coming to Jesus when he calls. “Sometimes," Dr. William Barclay, writing on this passage, observes, "we have a longing to abandon some habit, to purify life of some wrong thing, to give ourselves more completely to Jesus." Sadly, we do not always act on it that moment –"and the chance is gone, perhaps never to return" (Barclay,

The Gospel of Mark, Revised Edition, pg 261). After all, Jesus passed through Jericho only once.

Once he is standing before Jesus, our Lord calmly asks him, "What do you want me to do for you?" (Mk 10,51) The blind beggar’s response is our third lesson. Bartimaeus humbly, yet directly, says, "Master, I want to see" (Mk 10,51). Too often we have nothing more than a vague attachment to Jesus. However, when we go a doctor we want her to deal with some definite situation. When a toothache drives us to go to the dentist we do not ask him to dig into any tooth, just the diseased one. It should be the same with Jesus, healer of our souls. However, this involves one thing few people wish to face – rigorous self-examination. When we call to Jesus, if we are as definite as Bartimaeus, things will happen.

Indeed, things

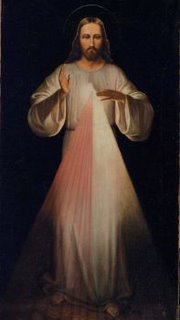

will happen. Do you believe this? Well, Bartimaeus did and his faith is our fourth lesson. As a blind cast-off, Bartimaeus would have been poorly educated. He may have been physically blind, but spiritually Bartimaeus had 20/20 vision. He demonstrates this by calling Jesus a Messianic title, "Son of David." Therefore, his conception of our Lord was as a king in the line of David who would lead Israel back to national independence and greatness. Of course, this is an inadequate idea of Jesus, the king whose kingdom is not of this world (

Jn 18,36). Still, Bartimaeus had faith, he believed that Jesus could and would make him see, such faith more than makes up for the inadequacy of his theology. Hence, the demand is not that we fully understand Jesus Christ. Rather, the demand is for faith. It is important to note that Jesus tells Bartimaeus his faith has

"saved" him. The Greek word here for

"saved" is

sozo, which means to rescue from danger or destruction. In short, Jesus is well aware that there is more ailing Bartimaeus than blindness. Saving faith begins with our encounter with Jesus and involves nothing more than returning the love God gives us in him. This encounter does not leave us unchanged. It leaves a mark. On-going conversion is the fifth and final lesson of the blind beggar.

Mark tells us that "immediately" after Jesus speaks, Bartimaeus "received his sight" and, having received his sight, follows Jesus "on the way" (Mk 10,52). On the way to where? He followed Jesus on the way to Jerusalem, to the site of the Savior’s passion, death, and resurrection. In other words, once his need was met, he did not go selfishly his own way, which, we know from Jesus’ words, he was free to do. No, he began in need, went on to gratitude, and finished with loyalty. That, my sisters and brothers, is a perfect summary of the stages of discipleship.

We are all blind beggars. The question is, do we sit beside the road in hopelessness and despair, or do we, like Bartimaeus, cry out, "Lord Jesus Christ, Son of God, have mercy on me, a sinner"? Do we pray in the confidence he will hear us, heal us and lead us on the way to our Father’s house, the heavenly Jerusalem?