If we make a hard and fast distinction between soul and body, with an eye toward separating them completely, we will wind up with some form of gnostic understanding, a heterodox belief, which will lead to heterodox practices. Whenever we discuss gnosticism, we must keep in mind, as Msgr M. Francis Mannion, a mentor and a man I deeply admire and without whom I would not be a deacon, writes in one of his Pastoral Answers columns for Our Sunday Visitor : "Gnosticism is such a complex reality with so many expressions that I can only give you a general description". As to the spiritual vs. the material, an opposition any healthy theology seeks to overcome and integrate, constitutes the very heart of the various gnostic ontologies, Msgr. Mannion writes, "The Gnostic sects thought the universe to be fundamentally evil. The end of all things was the overcoming of the grossness and depravity of the material and created order and the return of the soul to the Spirit-Parent facilitated by some God-sent savior. In that sense the Gnostics were pessimistic about the world", including, I might add, human beings. Again, universal among the gnostics, Christian, non-Christian, and pre-Christian, were the beliefs that spirit and matter are separable and that spirit is superior is matter. Their practices, flowing from their beliefs, were designed to liberate the spirit from the body. The goodness of material creation is essential for a sacramental view of the world.

This brings us to Christianity and the issue of total depravity. The Calvinistic doctrine that tells us, because of the fall, we are capable of no good apart from God. In other words, humanity is totally depraved. This is a major Protestant theology, which has different iterations. That is what makes my treatment far too simplistic. The belief in the total depravity derives from the theology of John Calvin, and is also called Reformed theology, which is on the rise in the U.S. these days. Reformed theology is the major influence among Presbyterians and Baptists, among other Christian denominations.

John Calvin

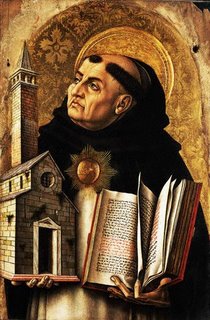

The other significant strand of Protestant theology for my far too simplistic purpose in this post is that of Martin Luther. It is more positive toward the human person than is Calvinism, but less so than Catholics in general, who largely take our cue from St. Thomas Aquinas. It is also important to note that among Catholics there are different theologies as well. The two major strains take find their roots in Augustine and Thomas Aquinas respectively. Since Luther, while a Catholic priest, was an Augustinian friar, it is not surprising that the Lutheran view of the human person is a variety of Augustinianism.

Martin Luther

Popes John Paul II and Benedict XVI gives us a ready-made example of the distinction between Thomism and Augustinianism, with John Paul II being a Thomist, thus having a more positive view of fallen humanity, while Benedict is more of an Augustinian, which is more pessimistic about people in terms of the basic goodness of fallen humanity.

St. Augustine

This difference is not due to any substantial disagreement between these two good friends and collaborators. In fact, the differences are complementary.

The difference probably arises from the fact that one is a Philosopher (John Paul II) and one is a theologian (Benedict XVI), as well as their cultural differences and their personal experiences in and of the world. In the end, neither Augustinians, including Lutherans, nor Thomists hold to total depravity as Calvinists and other Reformed theologies, theologians, and believers do.

It is important to get this right in order to live our lives in right manner, according to right reason. Orthodoxy=right belief or purity of faith and orthopraxis=right practice are inevitably linked. How we conceive of God, ourselves, each other, and the world matter tremendously. For these conceptions comprise the basis on which we live. We must also avoid the pitfall of thinking we know everything, or even thinking that we know and have experienced all we need to know and experience. We are and will remain beginners, mere children, but of a loving Father. Far from discouraging, this should encourage us, that is, give us the courage to walk with God. As beginners, we must begin. This far too simplistic overview, along with yesterday's class, constitute one small, but important, step. As Archbishop Donald Coggan, the 101st Archbishop of Canterbury, as quoted by Richard Foster in Celebration of Discipline, wrote: "I go through life as a transient on his way to eternity, made in the image of God but with that image debased, needing to be taught how to meditate, to worship, to think".

Based on all the above, I offer a prayer for today, inspired by Archbishop Coggan's remark and verses 1 and 2 of the twelfth chapter of St. Paul's letter to the Romans:

Lord, renew your image that is within us. Teach us how meditate in your holy presence, to worship you and you alone, not the idols fashioned by our actions and imaginations. Teach us to think by renewing our minds, that we may discern your will-what is good and acceptable and perfect, that we may present our bodies, which comprise your mystical Body, the Church, as living sacrifices, holy and acceptable to you, our spiritual worship. (see Romans 12,1-2).

No comments:

Post a Comment