The word atheist, like many of our theological terms, comes from the Greek language. The Greek word athos does not immediately denote a person who does not believe in God, it means a person who is lonely, a person whom God (in its original Greek context- the gods) has abandoned. This certainly rings true for us Christians. We believe that faith, which is our response to God, is a gift from God. As such, it is a theological virtue, along with hope and love. We believe that it is by God's grace that we come to faith, not by any decision we make. Of course, as with any gift, we must receive it. Nonetheless, there is a very real sense in which we just believe. This sense takes us beyond the resolution of intellectual issues and beyond the wondering, at times, whether there really is a God who loves us, who knows the numbers of hairs on our heads, and who is deeply concerned about us and involved in our lives.

By contrast, there are those who just do not believe. Such people bear no hostility toward those who believe in God. They tend to be suspicious of religion, as are many who believe. Of course, such a suspicion is certainly understandable. I do not intend to tackle formal atheism in this post with such logical arguments as the difficulty, or impossibility, of proving a universal negative like There is no such being as God, etc. Conscientious atheism and conscientious belief have a lot in common, as Archbishop Bruno Forte brilliantly pointed out in his J.H. Walgrave Lecture, given earlier this year at Louvain University, that I was made aware of by Rocco Palmo over at Whispers. It is entitled, Theological Foundations of Dialogue Within the Framework of Cultures Marked by Unbelief and Religious Indifference, which he concludes with these words:

"And, perhaps for the same reasons the thoughtful non-believer becomes conscious of the fascinating paradox of the prayer he cannot stop himself from saying: 'Grant us, o Lord, the paradises of nothingness, the gardens of your springtime. Lord, you make the night into a morning, the morning we pay for with the glittering coins of the stars, the stars of the night, guide of the wanderers, of the wanderers towards the infinite': what is heaven if not the infinite that journeys towards nothingness? What is nothingness if not a return, your return? What is the infinite if not a return?' In the restlessness of questioning, the faith of the believer meets the invocation of those who would like to believe: on the ground of a common poverty and of a common search, but also on the basis of listening to the other who dwells in the depth of both partners of meeting, dialogue between believers and non-believers is one of the highest and most enriching challenges of the cultures marked by unbelief and religious indifference, that are particularly those of our post-modern Europe. Shall we be ready as believers and as Church to accept this challenge without fear, with spirit and heart, trusting in the faithful God? On this question we must verify ourselves to make our choice in order to follow today, in our historical context, as persons and as Church, Jesus the living Lord."

Another, rather poignant, observation along these lines comes, once again, from Orhan Pamuk, who was last week awarded the 2006 Nobel Prize for Literature, from his novel Snow, in which Necip, a young aspiring writer, says to Ka, the poet, "A man could be at the coffeehouse every evening laughing and playing cards with his friends, he could have so much fun with his classmates that there is never a moment when they aren't exploding into laughter, he could spend every hour of the day chatting with his intimates, but if that man has been abandoned by God, he's still be the loneliest man on earth". To this Ka replies: "It might be of some consolation to have a true love." To which Necip sagely retorts, from the depth of an unrequited love he harbors for a beautiful girl "But only if she loved you as much as you loved her."

We long for love, not just to be loved, but we all really want to love with our whole selves. True, it is hard and it hurts to love, which makes it seem impossible a lot of the time. This why we must be reminded that God doesn't merely love us, "God is love" (1 Jn 4,8). Our deep longing to love, far from being unrequited, is always already there waiting, wooing, and yearning for us. God loves us, not only as much we love God, God is not so limited! Everyone, without exception and regardless of their beliefs or commitments, "who loves is begotten by God and knows God."

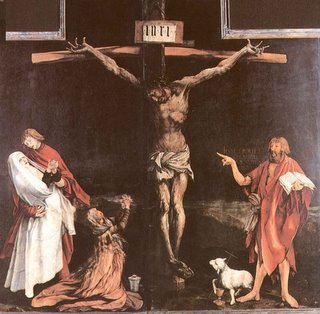

Matthias Gruwald's Crucifixion shows that the love, which is God, is not a syrupy, sappy, sentimental, unworthy love that ignores the darkness, abandonment, or cruelty of real life. No! With outstretched arms God embraces it all, he collects all misery and suffering, even death itself. Jesus, the High Priest, arms in the orans position, collects our loneliness that, at times, leads us to despair. He cries out with us in our agony, Eloi, eloi lama sabachthani!

Let St. Francis' prayer to the Crucified Jesus be our prayer today:

Look down upon me, good and gentle Jesus, while before Thy face I humbly kneel; and with burning soul pray and beseech Thee to fix deep in my heart lively sentiments of faith, hope and charity, true contrition for my sins and a firm purpose of amendment. While with great love and tender pity I contemplate Thy five wounds, pondering over them within me, calling to mind the words which David, Thy prophet, said of Thee, my Jesus: "They have pierced My hands and My feet; they have numbered all My bones."

No comments:

Post a Comment